The Cape Lookout Treasure

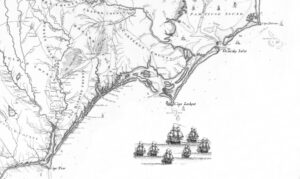

The Outer Banks of North Carolina can claim in its varied maritime history treasure stories that rival the best. Three ships of the 1750 Spanish fleet met their fate in a hurricane that delivered them to the Outer Banks.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina can claim in its varied maritime history treasure stories that rival the best. Three ships of the 1750 Spanish fleet met their fate in a hurricane that delivered them to the Outer Banks.

On August 18, 1750, seven ships cleared Havana, Cuba, for what appeared to be a routine trip home to Spain. They were loaded with treasure and other New World Commodities. On August 25th they encountered a hurricane near Cape Canaveral, Florida. The hurricane hit them in such a way that they were locked in the north bound Gulf Stream while being pummeled by the hurricane that pushed them up the American coast. Two of the ships, El Salvador and Nuestra Señora de Soledad, were totally wrecked upon Cape Lookout. The third, the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, escaped the ravages of the hurricane and safely anchored fifteen miles south of Ocracoke Inlet. Captain Juan Bonilla immediately began actions to preserve the one hundred chests of silver pieces of eight by getting them onto the beach at Core Banks, now known as Portsmouth Island. Afterwards, his galleon was towed safely into Ocracoke. San Pedro and the richest galleon, Nuestra Señora de los Godos, made it safely into Chesapeake Bay but were in such bad shape that they were condemned and the Spaniards hired other ships to carry their treasure back to Spain. The Nuestra Señora de Mercedes wrecked six leagues north of Cape Charles, and the escorting warship of fifty-six guns, La Galga, ran ashore on Assateague Island, Virginia, near the Maryland border.

For over thirty years treasure hunters have sought the elusive treasure of El Salvador lost on Cape Lookout. Spanish records document that there were sixteen chests of silver and four chests of gold valued at the time at 240,000 pesos. The gold alone would be worth many millions today.

Nuestra Señora de Soledad was reported to be carrying a cargo worth 32,000 pesos which included five chests in silver which was salvaged by Don Joseph Respaldiza, owner of the ship. The Soledad had come to rest near the south side of Old Drum Inlet. All of the crew survived and salvage of her cargo began immediately after the storm. Animal hides were taken from the hold and put in the sun to dry but became rotted and burnt in the sun. The grana (a valuable dye) spoiled and become a sludge with a dreadful stench and rendered worthless. The Soledad was set on fire as she lay on her side to facilitate further access to her hold. Respaldiza reported later that he was left with nothing, his ship and cargo are lost, “not even the clothing which I had loaded on the ship saved, neither were any of my papers …”

Records in the Archivo General de Indias record what was saved:

5 chests of coins – 14,467 pesos. A chest had been taken that had been stored in a cabin near the wreck site which contained 478 pesos

1 chest of silverware with a lamp for a church

6 sacks of grana

2.5 chests of wet sugar

250 hides which were ruined in the wreck

Not Saved:

16 sacks of grana

2 chests of earthenware jugs

655 hides

500 untanned hides

7 sacks of medicinal herbs

2,892 arrobas of sugar

122 arrobas of balsalm

Respaldiza’s salvage report indicates he got all of his silver. His expense account indicates that he spent thousands on the salvage effort, care and transportation of his crew, even support for Captain Bonilla at Ocracoke.

Finding the location of the wreck and the remaining treasure of El Salvador has eluded modern treasure hunters for decades. And for some, it has been a frustrating, if not fascinating, adventure. There are several accounts of how she wrecked and where she ended up. Because only three men and a boy survived, the reports of her loss are second hand and subject to interpretation. It appears that all of the accounts came through Respaldiza as it was reported that the survivors were brought to him at Drum Inlet. He in turn wrote a letter to Bonilla at Ocracoke informing him of his loss and the wreck of El Salvador. In the following accounts it is important to note that when the reports gave distances in leagues (three nautical miles) it was an estimate. If they said five leagues it could mean anywhere between four and six since they didn’t generally use fractions. To analyze the contemporary reports with the goal of locating El Salvador a chart of Cape Lookout must be consulted. One league equals about 3.45 miles.

On September 17, 1750, Captain Bonilla reported to the House of Trade. He had only been in Ocracoke Inlet for three days:

-

The frigate of Respaldiza ran aground on a sandbank twelve leagues to the south of where I am. All of the crew and the small amount of silver she was carrying and some skins were saved. However all the remaining cargo was lost as the frigate itself sank [submerged]. Five leagues further south of these, the paquebot of Don Jacinto de Arizon was wrecked on another sandbank. Only four lives were spared and the survivors said the ship had been carrying a valuable cargo.” “The Soledad wrecked five leagues northeast of the Arizon packetboat” was reported by Juan Bernardo Mayonde, first pilot of La Galga, in March of 1751.

-

On September 20, 1750, Bonilla wrote to Captain Huony of La Galga who had just arrived at Norfolk, Virginia. The message in that letter was reported on October 13, 1750, by letter from Joseph de la Cuesta y Velasco, purser of La Galga to the Marqués de la Ensenada in Spain. These valuable clues were found at the Archivo General de Simancas:

Bonilla wrote that he is at Cape Hatteras. He informed us that he had received a letter from Don Joseph Respaldiza in which he reported having gone on to a sandbank ten leagues to his southwest but the silver, some hides, and all the crew had been saved. The packetboat of Arizon wrecked further to the south and only four men had survived.” Another letter dated the same day, addressee and signatory unknown, said that “The packetboat of Arizon sank a few leagues distance from him and only three crew and a boy survived. They remained with Respaldiza´s men.”

- Pedro Pumarejo, captain of the Nuestra Señora de los Godos, writes to the Marqués de Esquilache from Norfolk on October 15, 1750. He had received information from Eusebio Martin De Cordoba, notary of the N.S. Soledad, who had travelled by horseback from New Bern, NC, for the purpose of getting assistance from him at Norfolk:

- Respaldiza had left the Soledad several days after she wrecked and went to New Bern in search of help. He found out that Governor Gabriel Johnston was at his home in Edenton so he travelled by horseback to meet with Johnston there. It is certain that the four survivors gave their account to him. It is not certain if the English did likewise, although it was most likely. The records show that Respaldiza needed an interpreter so he would not have gotten the information directly from the English. Governor Johnston, with the help of an interpreter, took Respaldiza’s report and forwarded it to the Board of Trade. His report, dated September 31, 1750 (Old Style Calendar September 20) reported that five ships of the fleet had been lost in North Carolina. It was fraught with errors:

“The packetboat, El Salvador, of Don Jacinto de Arizon, went onto a sandbank and came apart, the people all drowned except for three sailors and a boy and a cargo of cacao, sixteen chests of silver and four of gold. I have been told with certainty that on the same night, an English sloop ran ashore right beside it, it managed to get away and save some of the silver. Respaldiza is involved in the investigation as this misfortune was close to his [ship] and those that survived sought his protection.”

“One of these hit and broke up into pieces in the inlet of Currtuck (sic). The crew and passengers were saved and went to Norfolk in Virginia without stopping at Carolina.” [This ship was actually an English vessel. Dave Horner in his Treasure Galleons, attributed this wreck to be La Galga which actually wrecked on Assateague Island, VA.]

“Another sank off Cape Hatteras in 14 feet of water but neither the name nor the size of the ship is known, there is no information about the cargo she was carrying. “ [If a ship sank off Cape Hatteras it was not part of the Spanish Fleet.]

“Another ship, built in the Dutch fashion, lost her rudder and masts in Ocacock but the people were saved. Her cargo consisted of 400,000 pesos and a large quantity of red dye and hides.” [This is the Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe of Captain Juan Manuel Bonilla.]

“A ship called NS Soledad lost her masts and equipment in the inlet of Drum: her cargo is valued at 32,000 pesos aside from the ship itself. Her officials and crew have organized passages for themselves and their cargo to New England. From there, they will continue their trip to Cádiz.”[The Soledad did not actually wreck in the inlet because Respaldiza’s expense account later stated: “For the wagons used by the Englishmen at the site to transport all the things and people to the side of the bank– 199 pesos 6 reales.”]

“Another called El Salvador or El Enrique, broke up close to the inlet of Topsail and it is presently covered by six to eight feet of sand. Only four of her crew were saved. Her cargo consisted of 240,000 registered pesos aside from what was sent on private accounts. She also had a large portion of red dye, cacao and some balsam.

- Approximately late October 1750, Thomas Wright, a prisoner aboard the Guadalupe, gave his account to the South Carolina Gazette in Charleston. Records show he did not leave Ocracoke until October 19. The following was reported in the newspaper on November 16 (November 5th O.S.) “That on the 28th and 29th could be deemed nothing less than a great hurricane, in which the ships were separated. That on the 31st [probably meant 29th], they made the land about Hatteras (having no observation) when the weather being a little less boisterous and the wind shifted to the S.W. they came to anchor off the inlet, with two cables on end but rode hard all night, expected every moment to be driven ashore: That the weather being more moderate on September 1st, the Nympha (Guadalupe) rode it out.”

At Ocracoke, they were informed that Respaldiza was lost twelve leagues SW of that place, people and money saved, the Carthagena snow was ashore upon Cape Lookout. Most of her money was supposed to be aboard Ephriam & Robert Gilbert’s sloop (a Bermudian that had been driven ashore upon the same cape but had good fortune of being got off again.)

El Salvador at Cape Lookout

There is a possibility that most of the money was salvaged by the Gilberts. According to Bermuda shipping returns at the National Archives of England, a fifteen ton sloop registered to Ephriam and Benjamin Gilbert called Relief cleared Bermuda on July 21, 1750, loaded with salt for North Carolina. The Relief did not return to Bermuda until December 16, 1750, loaded with “fifty barrels of beef, a quantity of wrecked cocoa, old junk, and a hundred parcels of cedar timber.” The beef and the cedar timber were likely North Carolina produce that had been loaded before the storm. As reported by Governor Johnston, orders were issued to arrest the Gilberts and the sloop Relief. She no doubt fled as she was unaccounted for from September through November. Had the Relief recovered chests of treasure as reported it is hard to believe that the Gilberts would have reported it to customs in Bermuda. They had more than enough time to dispose of it in the Caribbean. On April 2, 1751, Thomas Gilbert shipped to London on the Southampton “42 casks of foreign cocoa imported from North Carolina from a Spanish wreck, one barrel of balsam, ten dry hides, one small bunch of copper, two bundles of seats for chairs, and 120 tons of foreign logwood” (the logwood had come from Jamaica aboard the Southampton). These items no doubt came from El Salvador.

Most accounts have El Salvador dashing to pieces on shore. The most important description said that the hull was covered with “6-8 feet of sand.” Anyone familiar with vessels at that time could estimate the draft of a ship merely by looking at her length. Records say that her depth of hold was nine feet. Since the hull was broken open (“went onto a sandbank and came apart,” see #4), all of her lighter cargo was liberated and floated ashore. When the seas retreated it appears by the description that the hull was nearly high and dry and buried. Otherwise it would be very difficult to determine the depth of sand on a submerged vessel or to burn her for iron fittings has had been reported. The reports of her treasure were widespread and certainly every effort was made at the time to recover what was left by the Gilberts, if any. This wrecksite was probably visited by many locals in the ensuing months because the word of Spanish treasure would have travelled fast.

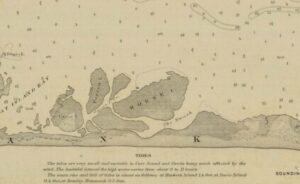

Reports (#1) said that El Salvador was “five” leagues south of the Soledad at Drum Inlet. By that description, the wreck could be on either side of the point of Cape Lookout.

Arguments for the left or west side: #4 El Salvador “broke up close to the inlet of Topsail.” And (#1) “…Five leagues further south of these, the paquebot of Don Jacinto de Arizon was wrecked on another sandbank.” The course along the beach is 21 miles from Drum Inlet to Topsail Inlet. As the crow flies its 17 miles. Five leagues equals about seventeen miles.

Arguments for the east side of Cape Lookout: #3 Captain Pumarejo reported “I have been told with certainty that on the same night, an English sloop ran ashore right beside it, it managed to get away and save some of the silver. Respaldiza is involved in the investigation as this misfortune was close to his [ship] and those that survived sought his protection. In #4, if you change the word “close” to “closer” in the following “Another called El Salvador or El Enrique, broke up closer to the inlet of Topsail” it takes on a new meaning. This statement followed the description and location of the Soledad given in #4 by Governor Johnston. This also becomes consistent with the statement found in #2; The packetboat of Arizon wrecked further to the south and only four men had survived.” And, “The packetboat of Arizon sank a few leagues distance from him and only three crew and a boy survived. They remained with Respaldiza´s men.” None of the testimony mentioned the little town of Beaufort. Beaufort, founded in 1709, lie just inside Topsail inlet and not far from where some testimony would place the wreck. It was the closest center of civilization.

All three ships, Guadalupe, Soledad, and El Salvador, were driven ashore by the winds of the hurricane. Using a variety of records it is possible to deduce the path and speed of the hurricane on the fatal day and night of August 29th. By taking a closer look at the winds themselves and the projected path of the hurricane, the probability of El Salvador being on the east side of Cape Lookout increases radically. Using the log books of HMS Scorpion anchored in Charleston harbour and HMS Triton anchored in York River, twenty-five miles north of Norfolk, VA, and the descriptions of the storm provided by Captains Bonilla, Pumarejo, and Huony, an accurate projection of the path and speed of the hurricane can be formulated.

At about noon on August 25, 1750, the fleet was hit by the hurricane at latitude 28° 51” N. This was northeast of Cape Canaveral, Florida. By the description of the winds going completely around the compass we know that they encountered the eye of the hurricane. It would not be until August 28th that HMS Scorpion at Charleston would record the effects of the storm. At noon, the ship’s log noted gales and squally weather from the north-northwest. At York River, off of Gloucester Point, HMS Triton noted squally weather with variable winds which would set in at northeast. The ships of the fleet were all being driven northward by winds from the southeast which meant that the fleet was northeast of the eye. The eye of the hurricane would have been approximately forty-five miles south east of Cape Fear, North Carolina at noon on the 28th. The distance travelled by the hurricane from noon the 25th to noon the 28th is estimated to be about 375 miles. The speed of the hurricane can be inferred to be about 5.2 miles an hour. This was a slow moving storm.

At noon August 28 the hurricane was about forty-five miles southeast of Cape Fear, North Carolina

The Guadalupe and Los Godos encountered each other at eleven in the morning of the 28th. They knew they were being driven towards shore so they turned with the wind to avoid the coast. The two ships became separated again. The Guadalupe was driving towards shore while Los Godos was caught in a different sector being propelled around Cape Hatteras. La Galga, San Pedro, and the Mercedes also made it safely past the notorious cape. Los Godos recorded encountering the eye of the storm shortly after noon on the 30th. At noon on the 31st they were at latitude 36 41”N, about fifty miles south east of Cape Henry at Chesapeake Bay and 100 miles north east of Cape Hatteras. The log of the Triton continued to record easterly gale winds on the 30th which changed to north-north-west and clear at noon on the following day. A merchant captain who witnessed the storm in Norfolk on the 30th said a great many vessels were drove ashore. The speed of the storm rapidly increased its northern track as the Maryland Gazette reported that Annapolis, Maryland, on the west side of Chesapeake Bay, was hit by a violent north-easter on the afternoon and night of August 30th raising the tide “higher than has been known for years.” Because of damage done to shipping south of Cape Henry on the 29th and the east winds recorded by the Triton at noon on the 30th, it appears that the eye of the storm passed about 35 miles east of the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. In two days it travelled about 240 miles, or about five miles per hour.

It is unclear exactly when El Salvador and the Soledad ran ashore. From captains reports on wind directions and storm intensity and using the British naval logs to plot the hurricane track, it is reasonable to assume that the seven ships of the fleet were relatively close to each other but out of sight with the exception on Los Godos and the Guadalupe which sighted each other briefly at 11am on the 28th.

Captain Bonilla of the Guadalupe reported being driven towards shore after sounding 110 feet of water. He had to be north of the point of the cape, otherwise he never would have cleared it. His first report to the House of Trade was in mid-September where he gave the date of August 30th. This was impossible because the eye is documented as being south of Cape Henry at noon on the 30th. It is his statement and that of Thomas Wright, his English prisoner, that later in the day they were driven by southwest winds before anchoring south of Ocracoke Inlet that confirms the date of the 29th and that the eye passed over Cape Lookout.

With Bonilla anchored three miles from shore at 6pm on the 29th, it must be concluded that El Salvador and the Soledad wrecked sometime on the 29th.

Noon, August 29, 1750

From what was reported, it appears that El Salvador and the Soledad ran ashore in the evening of the 29th. This was the height of the storm when Cape Lookout was experiencing onshore winds. From #3: “I have been told that on the same night, an English sloop which could have gone out to get some of the silver, also sank close to [El Salvador]. In this way Don J. Respaldiza was discovered as the sloop had been lost so close to his [ship] and those who survived came to his assistance.”

The Gilberts’ sloop, Relief, must have grounded during their salvage attempt on the Salvador and would only have been attempted after the winds switched to the northwest when the eye of the hurricane had passed to the north thus flattening out the ocean waves. That would have been after 6 pm on the 29th. The Relief probably was able to get off on the next high tide. Because of the proximity of the Soledad and the Guadalupe (Guadalupe anchored fifteen miles north of Drum Inlet where the Soledad wrecked) and the fact that El Salvador wrecked somewhere on Cape Lookout it is certain that El Salvador was close to the Soledad when the eye crossed Cape Lookout about noon on the 29th. For El Salvador to drive ashore to the west of the Cape, it had to occur prior to noon in the hurricane model presented.

By August 30, 1750, El Salvador and Soledad had wrecked upon Cape Lookout. The Guadalupe rode safely at anchor

After that, she would have been limited to going ashore on the east side of the cape. The strongest argument for El Salvador to be on the east side of the cape comes again from #3. Here it says that the Relief discovered Respaldiza. If they had gone out of Topsail Inlet to salvage the Salvador, they would not have discovered Respaldiza. Furthermore, the Relief would have had to cross the dangerous shoals that extend twenty miles out from the point. On the other hand, if the Relief went through Drum Inlet en route to the Salvador, the Gilberts would have passed Respaldiza and the Soledad along their way.

Anyone wishing to hunt for the treasure of El Salvador, if any is left, would need to get permission from the federal government because it is almost a certainty that her remains are buried in the beach today just as they were two and a half centuries ago.

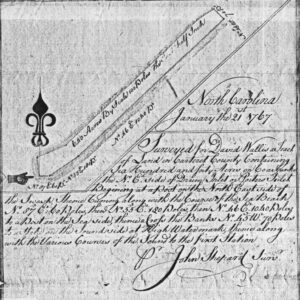

A plat of the island lying on the northeast side of Drum Inlet

one Core Banks was made in 1767 for 640 acres to David Wallis. Overlaying the plat on a modern chart shows that there is little difference today in the width of the beach compared to the 1767 survey. This demonstration may indicate that the beaches, at least away from the point of the cape, have changed little. Recent hurricanes however have accelerated erosion in these areas. If it continues, perhaps El Salvador will be exposed.

The Outer Banks Treasure Hunters

The range of search for El Salvador. Most analysis says that the wreck should be on the east side of the Cape

Alan Riebe, a North Carolina native, began his search in 1982 and continued sporadically over twenty years. Alan and I crossed paths in 1982. We had both been looking for La Galga off the beaches of Assateague Island, Virginia. Since he was moving on to El Salvador we agreed to share what little information we each had at the time.

Later, in 1986, Phil Masters of Intersal, Inc was searching in the vicinity of Beafort Inlet (Old Topsail) and focused on an area several hundred yards from shore in twenty two feet of water. In 1996, he discovered Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge . But El Salvador eluded him.

Riebe filed claim to a wreck he believed was El Salvador in 1987. The site yielded many artifacts such as a ship rudder, ballast stone, a small cannon, and other artifacts. No coins were found. He had two locations in mind: One at the west side of Cape Lookout Point and the other at Shackleford Banks, east of Topsail Inlet. For years Riebe not only had to contend with bad weather and limited visibility but interlopers as well. He had competitors who would stop at nothing to beat him to the gold.

One of his competitors was Frederick Luytjes who had worked with Riebe before he went on his own with Aqua Gems of the Treasure Coast and obtained a permit from North Carolina to work off Cape Lookout in an area that he claimed Riebe had abandoned. Riebe had the issue decided in federal court which ordered Luytjes to abandon his search in the area.

In 1994, Gordon P. Watts, a seasoned archaeologist and professor of maritime history at East Carolina University, organized a non-profit venture called the Institute for International Maritime Research in Washington, NC, and obtained a permit to search the waters from Beaufort Inlet (Old Topsail) to the inlet thirty miles west called today New Topsail inlet. After covering six square miles, the veteran explorer had no luck and gave up. His venture, like all of the others, remained in the “non-profit” category.

There are still more who joined the hunt. Dennison Breese’s group, El Salvador Partners; Mike Maquire, and in 2008, Odyssey Marine Exploration contracted with Intersal for rights and research Intersal had acquired during its fruitless search for El Salvador.

The Treasure of the 1750 Fleet is not Gold and Silver.

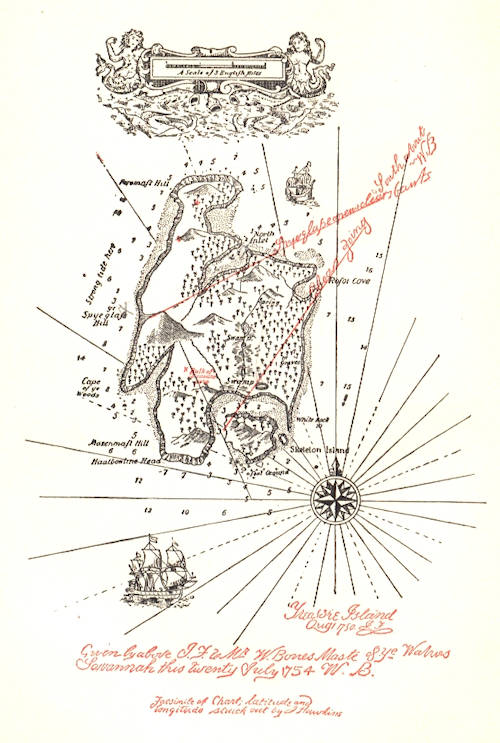

Treasure map dated August 1, 1750, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island

The preceding narrative was largely about El Salvador and her treasure. Ignored by most treasure hunters is the story of what happened to Captain Bonilla after he got the Guadalupe safely into Ocracoke. Bonilla’s hoard of silver was stolen by two merchant captains from Hampton Roads, VA; Owen Lloyd and his one-legged brother, John. On November 13, 1750, Owen Lloyd buried fifty chests of treasure on Norman Island in the British Virgin Islands. One hundred years later, to the day after this historic event, Robert Louis Stevenson was born on. After ten years of research in the archives of Spain, England, Denmark, The Netherlands, Scotland, Wales, and the archives of the U.S. and the Caribbean, this story has been faithfully retold in Treasure Island: The Untold Story. Treasure Island was real!

The 1750 fleet has yet another claim. Legend says that the wild horses of Assateague Island made famous in Marguerite Henry’s, Misty of Chincoteague, swam ashore from La Galga. This story is documented in The Hidden Galleon: the true story of a lost Spanish ship and the legendary wild horses of Assateague Island.

Two ships of the 1750 fleet have generated two classics in children’s literature. The events of 1750 reach even further. If it had not been for Treasure Island, there would be no Pirates of the Caribbean movies today. And without the events that took place at Ocracoke on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, there would have been no Treasure Island for Mr. Stevenson.

Long John Silver and the Outer Banks

1750 piece of eight minted in Mexico City. Usually packed three thousand to a chest. El Salvador had

sixteen chests on board when she wrecked on Cape Lookout.

Any silver piece of eight or gold doubloon found on Cape Lookout with the date of 1750 can now claim association with Long John Silver’s hoard which was buried in 1750. Any coins discovered will provide another link between the Outer Banks and Treasure Island. Gordon Watts placed a great deal of historical significance on El Salvador when he searched for her treasure in 1996. With the federal government’s mandate to identify all historical assets within their jurisdiction, perhaps the National Park Service will someday resume the search for her.